At first, things didn’t look that bad for the newly-minted king of Bohemia, Elector Palatine Frederick V. But the initial international recognition of other Protestant powers wasn’t much of a help when the new king ran short of money…

In the meantime, Ferdinand rallied his helpers round him. He had reached an agreement with Maximilian, Duke of Bavaria, as early as 8 October. Maximilian promised to provide the emperor with an army. In turn, Ferdinand ought to confer Frederick’s title as Elector Palatine upon Maximilian after Frederick had been defeated. The legitimization of that procedure against ‘rebellious’ Frederick resulted in a meeting of the imperial party at Mulhouse in March 1620, where it was decided that Bohemia was a part of the empire and Frederick had broken the imperial peace when he accepted the illegal election to become king of Bohemia.

Ulm. Reichsthaler, 1620. Dav. 5903. From auction sale Künker 194 (2011), 3721.

On 31 July 1620, the Protestant Union signed the Treaty of Ulm with the emperor, thereby assuring the ruler of their support for being promised in turn not to be dragged into the conflict.

Medal on the Confoederatio Bohemica. The crown of the alliance rests on the five countries Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia, which are all depicted as columns. Rev. The different religious parties, separated by the Word of God. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 213 (2013), 4029.

The financial situation in Bohemia became desperate already at the height of summer. Ernst von Mansfeld didn’t receive means anymore to finance his army. More and more soldiers deserted from besieged Pilsen, made straight for Prague and caused fear amongst the ordinary citizens which was a considerable damage to the new king’s image. In addition, the troops of the Catholic League, consisting of 25,000 men, led by Count Tilly, crossed the Bohemian border on 26 September 1620. Ferdinand’s allied forces of the Elector of Saxony invaded from the north on 5 October and besieged Bautzen. Only some days later, the imperial army stood in front of Prague where the forces commanded by Thurn had withdrawn to. That army, financed by the Bohemian estates, was to be the only one fighting on behalf of Frederick V.

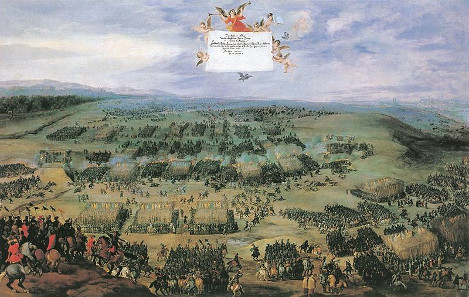

Pieter Snayers, Battle of White Mountain, 1620. Source: Wikicommons.

The mercenaries led by von Mansfeld declared themselves free of their contracts due to the back wages, and the cavalry Bethlen Gabor had sent as aid proved to be more an obstacle than any help because of their ill-discipline. On 7 November 1620, the imperial troops prevailed in the Battle of White Mountain. Frederick V escaped before the exacerbated citizens of Prague were able to hand him over to his enemies. Maximilian of Bavaria, in the name of Ferdinand, accepted the defeat of the Bohemian estates on 9 November. Strictly speaking, that would have concluded the war, unless…

Bohemia. Frederick of the Palatinate. Kipper-48 kreuzer 1620, Prague. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 153 (2006), 3031.

Frederick V had breached the imperial peace. That had been stated unambiguously at the Mulhouse meeting in March 1620. Technically speaking, being a traitor, Frederick had forfeited all of his lands. That was just what the Spanish Habsburgs had waited for. They provided the emperor with mutual assistance, and on 23 June 1620, the marching orders for Spanish troops under Ambrogio Spinola were signed whose task it was to secure the last 80 kilometers of the Protestant bank of the Rhine as deployment zone for the war against the Netherlands.

Peter Paul Rubens, Ambrogio Spinola, c. 1630. Source: Wikicommons.

On 19 August 1620, Spinola occupied Mainz. Maurice of Orange, who was just preparing the defense of the Netherlands, was worried by the loss of that important city. He asked his father-in-law, the English king, for help, who, in turn, sent 2,000 volunteers commanded by Sir Horace Vere who entrenched themselves in two key fortresses, i.e. Frankenthal and Mannheim. That took place not a moment too soon. On 5 September, Spinola left Mainz and crossed the Rhine, on 10 September he took Kreuznach, and four days later, on 14 September, Oppenheim.

Even if there had been a chance for peace after Frederick’s defeat in Bohemia – the Spanish wouldn’t have reacted. Their goal was to seize and secure Rhenish Palatine. To their profit, Frederick V refused to abdicate as King of Bohemia. Once the leader of the mercenary soldiers, Mansfeld, took sides again with Frederick – due to the lack of any other master – likewise a military pretense had arisen to leave the Spanish troops stationed in the Palatinate.

On 6 February 1621, the remaining members of the Protestant Union gathered. They wanted to discuss actions now that the emperor had outlawed Frederick on 29 January. The discussion ended without any result; and when the Spanish troops conducted a military exercise that was intended – and understood – as threatening gesture, the gathered princes backed down, accepted outlawry provided they would be granted neutrality. For the very last time the Union met in Heilbronn, and it can’t get any clearer than this how helpless the Protestant opposition in the empire acted at the early stages of the war.

After the Protestant rulers hadn’t been able to force Ferdinand to expel the Spanish troops from German imperial territory, the Netherlands considered themselves seriously threatened. On 9 April, the truce with the Spanish expired who had secured their line of supply along the Rhine by that. Maurice of Orange realized that he had to take more significant steps than mere diplomatic efforts. Thus, he agreed to finance the army of Mansfeld so that Frederick – with the aid of Mansfeld – could win back his ancestral homeland and prevent the Spanish from getting into the Netherlands.

By that, the war-related events had completely moved to the Rhine. Bohemia was of no interest anymore. Ferdinand didn’t meet any international resistance when he made the lands of the Bohemian crown bow down to his idea of absolutistic power, when he relieved the Protestants of their offices and disseized the rebels.

Bavaria. Maximilian I. Kipper-120 kreuzer (thaler), 1621, Munich. Hahn 78. From auction sale Künker 116 (2006), 4485.

The help the Bavarians provided in the course of these ‘acts of pacification’ and in the fight against the troops confederate with Frederick V, however, turned into an obstacle to peace: the Spanish Habsburgs, after the Palatinate had been secured and in order to concentrate on their Dutch conflict, wouldn’t have disliked the idea of humiliated Frederick V being reinstated into his office again under their supervision.

Ferdinand, however, couldn’t admit that because he wouldn’t be able to repay his war-related debts to Bavaria by transferring both Electorate and Palatinate. And so the war continued.

In the next episode you will read about Frederick V winning new allies, like the ‘mad Halberstadter’, and the military commanders Tilly and Mansfeld conducting a race that seemed to decide on the war’s victory and defeat…

You can find all parts of our series here.