A relic from Germany’s post-war era: a hoard of cigarette boxes

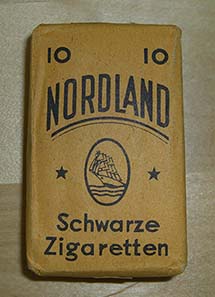

Time and again the happiness has been described a collector experiences when at a coin fair he finds the one, the small and seemingly insignificant object that nobody else recognizes. Something similar happened to the author on a flea market in the city of Staufen at the foot of the Black Forest. Among the masses of old dishes and tattered novels a small container laid filled with old cigarette boxes. When asked, the sales woman replied that she lived on a farm and that she had found these boxes lying on a heap.

A hoard of cigarette boxes.

The situation was quite clear: we were facing a hoard of currency, albeit an unusual one. They were specimens from the post-war era when cigarettes used to be Germany’s unofficial means of payment. May be the farmer had traded them for potatoes, eggs and butter. Since he possessed food, he had become such a “rich” man that he was not forced to instantly barter all cigarettes for commodities but hide some boxes in a small hoard for worse times. The Monetary Reform suspended cigarettes as “currency”. The farmer, perhaps not even a smoker himself, forgot about his small treasure that was only found half a century later by a descendant who offered it for sale on the flea market.

During and after World War II, smoking had become a common means of fighting hunger. This is illustrated by a note of the state’s council of the American Zone to the military government: “In present-day Germany, tobacco is not only a luxury foodstuff but first and foremost a pacifier and a means of distraction from hunger and worry.” The major part namely of the female smokers only began during the war or shortly thereafter to wallow in that vice. Hence, the number of potential cigarette consumers had greatly increased.

The German cigarette production and, later, the official import of American cigarettes did not meet requirements at all. Because of this, so-called smoker’s cards were introduced as early as 1940 designed to regulate the distribution of this scarce ware. This system was kept alive until 1948. The allotments, however, were not sufficient for a heavy smoker. In 1945, for example, he only got 40 cigarettes a month. To actually meet his requirements, he had to trade cigarettes on the black market. The cigarette as a durable and standardised, sought-after and not in endless supply available medium of exchange therewith had become an ideal currency substitute.

| Some prices in cigarette currency: 1.5 kg bread or bread ration food stamps → 10 cigarettes 1 chicken → 30 cigarettes 100-150 g meat or meat ration food stamps → 10 cigarettes 1 quilt cover → 125 cigarettes 75 g butter or butter ration food stamps → 10 cigarettes 15 g ground coffee → 10 cigarettes 25 g tea → 10 cigarettes 250 g sugar or sugar ration food stamps → 10 cigarettes 1 goose → 250 cigarettes Hence, our little hoard represents the equivalent value of 4 ¼ chicken or a quilt cover plus 15 g of ground coffee. |

Anything could be acquired for cigarettes in post-war Germany. The difference between prices for American cigarettes – in the USA 1.000 cost roughly $5 – made the “amis” the most popular contraband. They arrived with the packages the allied soldiers received from home. Customs investigation regarded the former concentration camp Bergen-Belsen the reloading point for this illegal ware; primarily Jewish Displaced Persons lived there trying to finance their emigration to Palestine by contraband. It was only in May 1947 that the import of cigarettes by post was prohibited – thereafter, it was not even allowed to put them in the very popular CARE packages. This measure was designed to fight the black market – but with no success whatsoever.

The American-blend-cigarettes, especially the trademarks Lucky Strike, Chesterfield and Camel, were the most popular because with their blend they fought hunger most effectively. On the black market, therefore, one got 5 to 40 Reichsmark for an “ami”, in contrast to 3 to 12 Reichsmark for a German cigarette – quite a lot of money all the same; after all, in 1946/47 a German worker working in the luxury food industry earned 96 Reichspfennige an hour, officially he had to pay 16 for a German cigarette. An average worker, then, had to work roughly 7 hours to pay his 40 cigarettes per month.

A box of cigarettes produced in the city of Lahr.

The “cigarette hoard” presented here consists solely of cigarettes produced in Germany – even though the “amis” dominated the market, Germany’s own production did not come to a halt altogether. In the upper Rhine valley tobacco is cultivated up to the present day – until recently, the tobacco continued to be used for the production of cigarettes: until 2006, the Lahr / Schwarzwald so widely known from our boxes housed a Reemtsma cigarette factory.

German citizens could deliver their tobacco to factories like this one since the cultivation of tobacco plants had become a widely popular hobby in the post-war era. In those days, no less than two third of the smokers grew their tobacco on the balcony and in the front garden to counter the grave shortage. In 1943, up to 25 plants were tax-free, whereas since 1946 only 15 plants were allowed officially – but that did not stop anyone to grow more. The cigarette company, however, only traded the legal amount of tobacco for cigarettes. The rest of the harvest was dried on a baking tray at home, flavoured with wine, vinegar, sugar or plums – with the trademark “Siedlerstolz“ (“settlers’ pride”) or „AEG“ (=from the own garden) the air was polluted afterwards.

Cigarettes of the Bosco brand.

What makes our cigarette hoard so interesting is the fact that the hoarding of cigarettes follows the same principles we can observe with coin hoards. A major part of the hoard consists of local “circulation currency”, that is of small cigarette boxes made in the vicinity with some foreign “sprinklings” from a longer distance or from the wider past. Two such examples may be the package from Dresden that presumably was made during the war and the one of the Bosco trademark that found its way from the French Sector to Staufen.

It is safe to assume that only very few visitors the Staufen flea market had realized that the small jar contained an extraordinarily rare testimony of our own past that most of us – even though not eye-witnesses on the post-war era – are still familiar with due to the stories we heard from older relatives.