March 22, 2012 – German monthly inflation topped 29,500 % in 1923; France had to let its currency depreciate by 93 % against gold and silver between 1914 and 1939; Hungary experienced the highest rate of inflation ever reported: 4.19 1016 % in July 1946. The 20th century witnessed the radical impoverishment of Europe at the hands of inflation as well as its worst succession of economic and political crises. With no significant inflation in the developed world since the 1980s, the recent economic turmoil has nevertheless managed to revive these old fears, pushing gold prices spectacularly higher.

Brazil (Pedro I). Inscribed ingot, 1830. Gold, 167.22 grams. Serro Frio. Obverse: crowned arms of Portugal; 23.25 carats, 5 onças, 6 oitaves 54. These ingots were produced in Brazil from 1778 to 1833 as pseudo-monetary objects, like the US gold issues of the California Gold Rush of 1848-1855. Stamps, seals and indications of weights and purity are present, as has been the norm since the time of the Romans. Most European and American countries followed the Gold Standard at this time, sometimes alongside silver through a bimetallic standard (ANS 1963.240.1, gift of R. Henry Norweb, Sr.). Image Courtesy American Numismatic Society.

The exhibition explores the world of inflation through the material, cultural, political, financial and artistic aspects of the nearly 200 objects on display. Ranging from the 7th Century BC to contemporary monies, they take the form of shell money, spades, ingots; wood, plastic and metal coins; bank notes, IOUs’, etc.

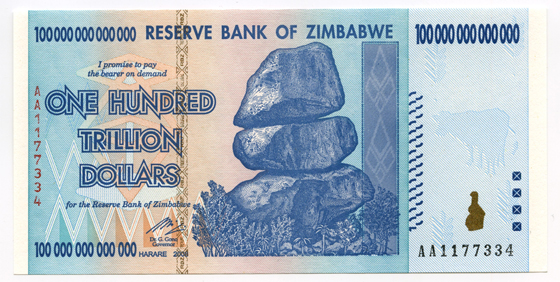

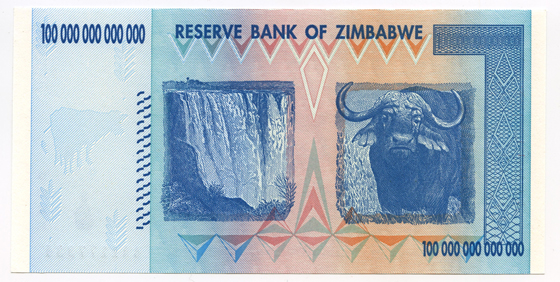

100,000,000,000,000 dollars, 2008, banknote. High inflation in Zimbabwe started in 2004, as the state had its central bank printing more and more money to provide resources for its strapped budget. Inflation reached 624% that year. The situation exponentially worsened and peaked in November, 2008, at a monthly rate of 79.4 billion %, or 98% on a daily rate. The Zimbabwean local dollar was dropped in April, 2009, in favor of using foreign currencies, mainly the US dollar – a paradoxical achievement. The peculiarity of the 100-trillion dollar banknote is the full display of all the 0s, something Hungary or Germany avoided, but which recalls the Yugoslavian practice (Loan of François Velde). Courtesy François Velde and the American Numismatic Society, NYC Zimbabwe.

The highlights of this exhibition include the highest denomination ever issued: a 1946 Hungarian banknote with 21 zeros, as well as the highest number of zeros effectively visible on a bank note, the 100,000,000,000,000 dollar bill issued in Zimbabwe in 2008. The US never issued anything with quite that many digits, although visitors will be able to admire the very rare 1934 gold-convertible high denomination series whose denomination reached as high as $100,000 while there was no inflation at all. The exhibition explores some other forms of inflation, like the cowrie-monies and Kissi-pennies that flooded 19th and 20th century Western Africa.

Inflation is intrinsically connected with situations of crises. As such, monetary objects issued during periods of inflation are often rich in historical meaning. The French Revolutionary authorities still minted coins bearing the portrait of Louis XVI long after his beheading, while the inflationary issues of Yugoslavia relied on heroic national characters to promote the patriotic spirit of a country that was dissolving itself through hatred and civil wars. Attempts to deceive the public are as old as the first forms of official currency. The sophisticated cultures of the ancient Near East did not issue a coinage, although they were commercially very active. People and authorities were happy to use miscellaneous metal objects in their dealings. It is in Asia Minor, where the supply of a gold and silver natural alloy called electrum could be found in abundance, that authorities decided to strike coins as sole legal tender.

Macedonia (Northern Greece), 1 drachm, c. 450 B.C. Silver, plated. 4.54 grams. Neapolis. This plated coin has been sliced, revealing the outer layer of silver that covers a copper or bronze core. Coinage of uncertain quality could be rejected by money-changers, effectively causing coins issued by states with poor monetary reputations to be traded at a discount – even when they were genuine silver, unlike this plated counterfeit from Neapolis. As such, price stability was imperfectly protected by an untrustworthy coinage (ANS 1934.86.12, gift of Dr. E. P. Robinson). Image Courtesy American Numismatic Society.

Through artificial silver enrichment, they ensured themselves a substantial source of profit. Plated coins from Athens and Macedonia, debased Roman coins, and contemporary base metal coins that keep the appearance of their silver predecessors, illustrate that phenomenon.

Electronic money may bring the history of material currencies to an end, finally replacing the intrinsic values of ancient monies in entirety, by the official charter linking citizens to their money. But the expectation of inflation will not disappear as long as divergent interests can possibly undermine the necessary social cohesion that supports monetary stability.

Also on view at the Federal Reserve Bank of York is the ANS’ long running exhibit Drachmas, Doubloons & Dollars: The History of Money, featuring over 800 pieces from the Society’s collection, including a Brasher doubloon, an 1804 dollar and a Confederate half-dollar, as well as the world’s most valuable coin – a 1933 Double Eagle (on loan).

More information on the exhibition you can find on the ANS website.