June 21, 2012 – “Gold: Power and Allure” is the most comprehensive and ambitious exhibition ever staged at Goldsmiths’ Hall. Until July 28th it powerfully tells the rich and previously untold story of Britain and its relationship with gold, demonstrating the country’s unique golden heritage.

Charles I, medal, 1642.

This major project showcases more than 400 gold items ranging in date from as early as 2500 BC to the present day. It includes rare and exquisite works of art, combining sophisticated artistry and skill, together with pieces of exceptional historic significance. Others are esoteric, curious and amusing. All the exhibits, displayed over three floors at Goldsmiths’ Hall, have been loaned from distinguished institutions and private collections and many have rarely been seen in public before.

Charles I, triple unit, 1642-1649.

This is the first time such an extraordinary group of objects has been brought together. It tells a story of passion and power, fortunes lost and gained, and the special place this metal plays not only in our national, but also our personal histories.

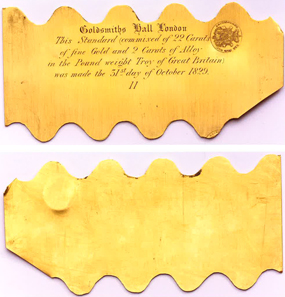

A so-called trial plate from 1649 to test the colour of the freshly minted gold coins to ensure its correct composition.

Historian Dr Helen Clifford, the curator of the exhibition, explains: “Gold: Power and Allure presents the opportunity of a lifetime. The challenge has been to draw together the many strands that make a single precious metal so special and central to human society.

“With the focus on Britain it has been possible to assemble a story that goes far back into geological time and forward to the most cutting edge goldworking, where this country excels.

“It reveals a story of the continuity of man’s fascination with gold, from the Bronze Age to modern City finance, via a breathtaking range of more than four thousand years of work. In essence it is a story of global connections and one where the familiar is transmuted into the iconic, via the power of gold.”

Coin Hoard.

Gold is one of the world’s most highly-prized precious metals. It is rare, soft, ductile, and malleable. Its colour, that of the sun; its untarnishing lustre and ‘heft’, its weight in the hand, mark it out as something special. Gold’s workability is unparalleled: it can be beaten into transparent leaves and cold welded by hammering allowing the craftsman almost limitless possibilities. Gold alone commonly occurs in a ‘native’ state, as a metal rather than an ore that requires smelting.

Surprisingly there are traces of gold to be found in almost every part of Great Britain, from the Strath of Kildonan in the Scottish Highlands, via Goldscope in Cumbria through Dolgellau and Pumsaint in Wales, where there is evidence of Roman mining, down to Hope’s Nose in Torquay and the Carnon Valley in Cornwall.

Discoveries of gold deposits have prompted “gold rushes” across the globe, yet few know of the Scottish gold rush. Prospectors flocked to Kildonan in the Highlands in 1869 and some of the finest fruits of their labours feature in the exhibition. One of the largest gold nuggets, weighing 59 grams (almost 2 troy ounces), was however discovered not in Scotland but in Cornwall – and is being loaned by the Royal Cornwall Museum. Very recent rock samples from Scotland and Northern Ireland show the search for gold remains very much alive.

The Gold of antiquity

It is a sobering thought that most ancient goldwork found in Britain has come to light by pure chance. Excavations for a new housing development in Amesbury, near Stonehenge in 2002 revealed the burial of two men, thought to date to 2300 BC. Each had a pair of small gold basket shaped ornaments laid near them. These are some of the earliest known examples of worked gold to be found in this country, although their precise use and meaning remain unclear.

Another exciting example of early gold work featured in the exhibition is a magnificent lunula dating from 2000-1500 BC, which was found in Northern Ireland on land then owned by the Worshipful Company of Drapers in c.1845/6. These distinctive early Bronze Age crescent-moon shaped pieces were hammered out of gold and thought to have been made to adorn the necks of tribal chieftans. Less than 200 gold lunulae are known and it is possible they were all the work of a handful of experts. Three of them from different sources are on display at Goldsmiths’ Hall. Without any supporting contemporary documentation these enigmatic objects continue to fascinate and puzzle.

It is somewhat ironic that the so called ‘Dark Ages’ should have produced some of the finest gold work ever made in these islands. The achievements of Anglo-Saxon goldsmiths were of remarkable accomplishment and beauty and, thanks to the practice of putting objects in graves, finds are well represented. Experiments with enamelling and stone setting can be seen in the early 7th century gold and garnet pendant from Canterbury Museum and the Harford Farm Disc Brooch from Norfolk Museums Service.

For the Medieval period higher end objects are exceptionally rare, an imbalance due to the nature of the objects themselves; many were made for the Church, chalices, shrines and reliquaries which failed to survive the Reformation. The exhibition presents a cluster of intimate and exquisite examples of medieval cabochon set gold brooches: the early 14th century Oxwich Castle brooch, the mid 14th century, ‘M’ brooch from New College Oxford and the now famous Middleham Jewel which was discovered by metal detector near Middleham Castle in North Yorkshire in 1985. It hit the headlines when it subsequently sold for an outstanding £1.3 million at Sotheby’s in London. The 15th century gold lozenge shaped pendant is intricately and intimately engraved with biblical scenes and set with a large sapphire, and has been generously loaned by the Yorkshire Museum.

Religion, royalty, and ceremony

For centuries gold has been both a pagan and Christian symbol of the divine, and has been used in religious ceremonies of all denominations. This continuity in the association of gold with divinity is captured via a range of golden objects from a Bronze Age sun disc found in Wiltshire, a communion cup made of Guinea gold for a church in Welshpool in 1662, to a chalice commissioned in 1958.

In a year which celebrates HM The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, the exhibition appropriately highlights the long association of gold with Royalty with several items being loaned from the Royal Collections. One of these is the Coronet of George, Prince of Wales, created in 1901-1902, for the then Prince of Wales (the future King George V) to wear at the coronation of his father, King Edward VII, in 1902. At George’s own coronation in 1911, the crown was worn by his son, Edward, the next Prince of Wales. When as King Edward VIII he abdicated in 1936 and (as the Duke of Windsor) went into exile in France, he took the coronet with him. It remained abroad until his death in 1972.

The importance, high profile and public presence of these objects mean that they are deeply embedded in historical documentation which allows us to recreate their meaning, use and symbolism in vivid detail.

Other more intimate objects associated with royalty include a gold ring taken from the finger of the dead Queen Elizabeth I, and a ‘touchpiece’ presented by Charles II for the curing of scrofula (The King’s Evil).

Gold and Finance

In the early 1890s Sir William Harcourt, while Chancellor of the Exchequer, celebrated the fact that London was considered the “Metropolis of Commerce”, largely because it was “the only place where you can always get gold. It is for that reason that all the exchange business of the world is done in London”. The story of Britain’s rise to financial power can be told in several ways, via the development and use of gold currency; the evolution of the Gold Standard and the role of the Goldsmiths’ Company in controlling the quality of gold and the standard of the currency.

2 pound gold coin of William IV, 1831.

The story of Britain’s gold currency is explored via a spectacular loan of historic coins from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. There are gold staters which were the model for early Celtic gold coins, the Roman aureus used in Britain before it had a Mint, the solidus which circulated via trade with the Byzantine Empire, to the coinage of Edward III. These are followed by subsequent nobles, riders, ryals and unicorns, to the 1489 Henry VII sovereign, the guinea employing gold from its West African source, and the new sovereigns of George III.

Virtually all the gold mined throughout the world during the 19th century was turned into coins, with the sovereign being the premier gold coin in Britain. These are complimented with an example of every gold coin produced during the reign of each British monarch from Edward III (1312-1377) onwards, with the exception of Edward V, emphasising the important role played by the Royal Mint.

A trial plate dated October 31, 1829 consisted of 22 carat of fine gold and 2 carats of alloy in the pound. These plates were used during the Trial of the Pyx.

The control of gold is investigated via Isaac Newton’s introduction of a Gold Standard (which was formally adopted in 1816, and only abandoned in 1931) and the role of the Goldsmiths’ Company. Many early goldsmiths were also bankers, and in 1282 Edward I requested the Company take responsibility for the quality and testing of the coinage by holding the Trial of the Pyx (Latin for moneybox), an annual event which still takes place today. In 1478 the London Assay Office was established at Goldsmiths’ Hall and the story of the hallmarks on gold is told via a succinct collection of objects and images.

Dining and Living

The crucial importance of dining as a means of signalling power and diplomacy has always been magnified through the use of golden tableware. Only those who aspired to the apex of society could afford to purchase gold rather than gilt. The gold ice pails c.1680-90 bequeathed in 1744 by the first Duchess of Marlborough to her grandson, and the magnificent ewer and basin made by Pierre Platel in 1701-2 for William Cavendish 1st Duke of Devonshire (from Chatsworth) are exceptional because they are made of gold. When the wealthiest commoner in England of his day, William Beckford wanted to affirm his status, he bought a gold tea pot and toasting fork to take on his travels.

Sporting gold

Heroism and gold have long been associated not least in the field of sporting and athletic excellence and achievement – the ultimate goal is to win a “gold” medal. In the year of the London 2012 Olympics it is therefore highly topical that sporting gold plays an important role in the exhibition.

Olympic gold medal of the men’s eigth during the VIII Olympic Summer Games in London in 1908.

Pure gold Olympic medals are in fact extremely rare and only four Olympiads used solid gold medals: Paris 1900, St Louis 1904, London 1908 and Stockholm 1912. Two rare examples dating from 1908 and 1912, both awarded to members of the same family connect one family’s triumph with international achievement.

Gold and military

From the sporting field to the battlefield, both on land and at sea, gold has long been used as a symbol of heroism and to record and commemorate significant victories. The resulting objects can be freighted with complex personal and cultural associations.

For example a sword with a gold, enamel and gem set handle was presented to Sir William Beresford by the City of London in recognition of his services in the capture of Buenos Aires in 1806. The “Nelson” snuff box, dating from the first half of the 19th century, decorated with a polychrome scene depicting a view of Genoa, was a gift to Admiral Nelson by General de Vins.

Gold for our time

The exhibition offers the unique opportunity to assess how goldsmiths working from the Second World War to the present have approached this special metal. The status and cost of gold means that our most celebrated and experienced goldsmiths have engaged with it. Look at the golden goblets and boxes of Gerald Benney to the laser cut breadbasket of Grant Macdonald, from the Downing Street Collection. The hand-raised forms of Hiroshi Suzuki sit next to the pioneering 23.9 carat micro alloy and laser welded jug made by Martyn Pugh in 2011. Techniques used from the Bronze Age combine with the latest technology to create treasures truly for our time.

The Goldsmiths’ Company “Gold Trail”

The influence and reach of the exhibition extends far beyond the boundaries of the City of London as a “Gold Trail” stretches across the breadth of the United Kingdom.

The “Gold Trail” charts every major gold collection and points of interest in regional museums, institutions and churches, both large and small collections and with varied uses. These include items too precious, fragile or large to be moved to Goldsmiths’ Hall. Examples of places and items featured on the “Gold Trail” include the Gold Palm Room at Spencer House, the Royal Cornwall Museum, the Scottish Crown Jewels, St. Cuthbert’s Cross, Durham, the Portland Gold Font and many, many more.

The exhibition will be accompanied by an associated book “Gold: Power and Allure” published by Paul Holberton.

For further information on the Goldsmiths’ Company, please visit its beautifully designed website.

Detailed information on the exhibition in Goldsmiths’ Hall are available here.

We also recommend a visit of at least the website of the Ashmolean Museum Oxford. You can browse many collections online!