Items found: Carsten Niebuhr reports on treasure troves in wild Kurdistan

translated by Annika Backe

In the service of the King of Denmark, Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) travelled through the Orient from 1761 to 1767. A Göttingen-based orientalist had suggested this trip, for he hoped that a scientific expedition could deliver hints that the Bible might be right after all. He got Danish King Frederik V enthusiastic about it, who then funded a team of five researchers and a servant. In his capacity as cartographer, Niebuhr also belonged to this team.

During the expedition, everybody except Niebuhr died. As the sole survivor he returned home, with, among other things, an exact copy of several cuneiform inscriptions he had made in Persepolis. These copies served as the basis for Grotefend’s decipherment of cuneiform writing.

Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815), drawing by Julius Fürst.

After returning home, Niebuhr published a number of books. One volume of the Erdmann edition harks back to these when he lets Niebuhr recount himself his trip through the Orient. We shall not keep from you an extract taken from this volume in which Niebuhr addresses rugged Kurdistan and what the people living there do with ancient coins:

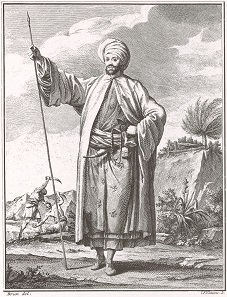

Portrait of Carsten Niebuhr wearing the local dress.

When I made inquiries about old Roman, Greek, and Persian coins in Mosul, I was informed that these coins were so frequent in Kurdistan, where there is a shortage on Turkish low-value coins, that they are taken as ordinary currency. The merchants, after all, use them for payment when they buy gall nuts.

If a Turkish pasha or qadi learns that somebody intends to sell old coins, this somebody is not only stripped of all his belongings but shoved in jail and beaten. Corporal punishment is frequently inflicted in Baghdad.

Old Arabic coins are not an unusual sight in the countries of the East. For it is fashionable here to adorn the neck of children with many rows of gold pieces, the Muhammadans rather take old coins, which bear words of the Qu’ran but not the name of the regent.

Many precious items are buried. It sometimes happens that people, even if they are on the sickbed already, do not reveal to their relatives where they can search after they have died. I was told that a Kurd only revealed to his son where he had stored his money when he was at death’s door. The only thing he still managed say, though, was the word ‘hill’.

The son conducted diggings on several hills, but he could not find anything.

For this extract we thank Dr. Burkard von Roda.

If you are interested in Carsten Niebuhr’s book (written in German) from which this passage was quoted, you can place an order by clicking here.