August 18, 2016 – Storms, War and Shipwrecks tells the story of the island at the crossroads of the Mediterranean through the discoveries made by underwater archaeologists. For 2500 years, Sicily was the place where great ancient civilizations met and fought. Its rich and varied island culture has been marked by the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs and Normans. This major summer exhibition explores the roots of this multicultural heritage with over 200 beautiful and unusual objects rescued from the bottom of the sea.

View into the exhibition. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

From bronze battering rams once mounted on the prows of Roman warships to the marble pieces of a Byzantine ‘flat-pack’ church; from intrepid prehistoric traders to the enlightened rule of the Norman kings, the exhibition illuminates the movement of peoples, goods and ideas.

Roman portrait heads. Lent by Museo archeologico regionale ‘Paolo Orsi’ di Siracusa. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

The treasures on show in Storms, War and Shipwrecks have been uncovered over the last sixty years since the advent of SCUBA diving equipment which made possible sustained underwater exploration. While some of the objects are chance finds pulled up by local fishermen, most are from shipwrecks excavated by archaeological divers.

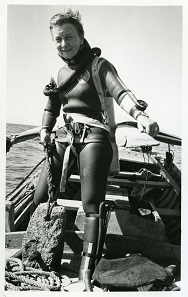

Honor Frost. Photo: © Honor Frost Foundation.

One of the earliest pioneers of underwater archaeology, whose legacy is explored in the exhibition, was the remarkable British woman, Honor Frost (1917–2010). Frost trained as an artist in London and at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford and she spent the first part of her career working as a designer in ballet. But her enduring passion was for diving. In her book Under the Mediterranean (1963), she describes how she started out as a young woman by submerging herself in a well at a home in Wimbledon using a garden hose. In the 1940s she began to train as a diver in the south of France. Her mentor was the French archaeologist, Frédéric Dumas, who took Frost on her first dive to the wreck of a Roman ship at Anthéor on the south coast of France.

Frost gained further experience working on land as an archaeological draftsman in the middle-east, and here she became convinced that the skills and methods practiced on land excavations could be adapted to maritime archaeology. She was involved, in the 1960s, in the first underwater excavations to use systematic archaeological techniques; and in 1971 she directed the excavations and recovery of a Carthaginian ship off the coast of Sicily.

ROV approaches amphora Photo: © Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali del Mare, Palermo.

Frost was instrumental in establishing marine archaeology as an academic discipline. Today divers use cutting-edge technology such as ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) to explore deeper and further than ever before. Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean and lying at the heart of historic maritime routes, is a leading centre for underwater archaeology.

Warship ram. Lent by Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali del Mare, Palermo. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

One of the most important discoveries to date has been made near Levanzo in the Egadi Islands off the northwestern coast. Here, since 2004, underwater archaeologists from the Soprintendenza del Mare and the RPM Nautical Foundation have recovered eleven Roman and Carthaginian warship rams. These powerful weapons, mounted on the fronts of ships, were designed to plough into enemy vessels with great force.

Montefortino helmet. Photo: © Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali del Mare, Palermo. Photo by Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Together with helmets and other debris, the rams are proof of the exact location of the Battle of the Egadi Islands fought between the Romans and the Carthaginians on 10 March 241 BC, providing a remarkable confirmation of the accounts given in ancient literary sources of this momentous naval battle.

View into the exhibition. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

In the exhibition, a display of several rams, accompanied by a digital reconstruction from the battle, will bring to life the decisive victory of Rome over Carthage, an event that changed history, ending the First Punic War between the two superpowers and ensuring Rome’s ultimate domination of the Mediterranean.

Byzantine Church ruin in Athrun. Photo: © Vincent MICHEL, French Archaeological Mission in Libya.

Another spectacular discovery which will be shown in the exhibition is an example of a Byzantine ‘flatpack’ church. The Emperor Justinian (c. 482–565), in his efforts to fortify and regulate Christianity across his empire, was a prolific builder of churches. Under his rule, based at Constantinople, large stone-carrying ships known as naves lapidariae, laden with prefabricated marble church interiors were sent out from quarries around the Sea of Marmara (the ‘marble sea’) to sites in Italy and north Africa. Remains of completed buildings can be seen today in Ravenna, Italy, in Cyprus and in Libya. But some of these ships carrying architectural pieces never made it to their intended destination. Heavy and slow, they became unbalanced and sank during stormy weather.

Marble pieces of a flat-pack church. Photo: © Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali di Siracusa.

In the 1960s German archaeologist, Gerhard Kapitän, excavated a shipwreck off the southeast coast of Sicily. Hundreds of prefabricated marble elements of a basilica were brought to the surface: 28 columns with Corinthian capitals and bases, choir-screen slabs and pieces of an ambo (pulpit). Much still remains beneath the surface and the site has been under investigation again since 2012 by the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project and the Soprintendenza del Mare.

CGI reconstruction of a Byzantine church. Photo: © Stan Verbeek VODAL Virtual Heritage Reconstructions.

The Ashmolean will use a selection of pieces to reconstruct the church interior in the final exhibition gallery, allowing visitors to experience the building which spent more than a thousand years on the sea-bed.

Reshef. Lent by Museo archeologico regionale ‘Antonino Salinas’ di Palermo. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Dr Paul Roberts, Keeper of the Department of Antiquities, Ashmolean Museum, says: ‘Visitors to this exhibition will be taken on a journey through Sicily’s fascinating history. Here at the Ashmolean, for the first time, this story will be told exclusively through spectacular finds from the sea, because it is the sea which has always been the lifeblood of the island’s unique and diverse culture.’

More information is available on the website of the Ashmolean Museum.

If you want to learn more about the history of Sicily, please read the CoinsWeekly Sicilian Mosaic series.

Please find here the numismatic diary Sicily in full bloom.

And a detailed account of the life and achievements of diver Honor Frost is given in her obituary published in The Guardian.