November 2, 2017 – Since the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, many countries around the world have adopted a form of communist government, by adapting Marxist theory to suit a set of diverse economic and geographic conditions. A form of communism has subsequently been brought to more than 20 countries around the world. Drawing on the British Museum’s remarkable collection, this display explores how money works and what it looks like under communism.

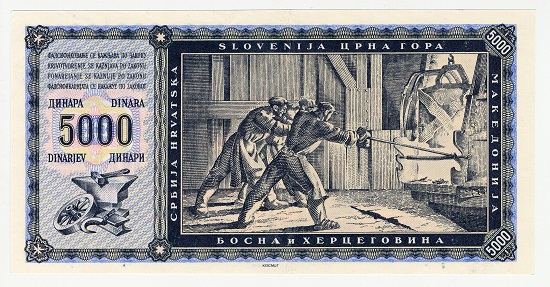

Yugoslavia, 5000 dinara, 1950. The foundry was a common motif in Socialist art, a metaphor for the forging of the communism state. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Another aspect of the project has been the acquisition of posters advertising banking services, government bonds, insurance and other themes relating to money. These are among the most visually striking of the acquisitions and have enhanced our understanding of how money has worked and how it is represented within different artistic media. A selection of the 400 or so acquisitions made so far with the Art Fund grant will be on display, as well as other objects.

China, People’s Bank of China, 50 yuan, 1980. These were the people who would lead the development of modern China: a farm girl, industrial worker and an intellectual. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Communism holds that money is a social construct, and has no role in a utopian society. However, no communist state has successfully eliminated money from its economy. Rather, concepts of value and wealth are eroded and distorted, while the national currency becomes just one of several types of exchange, both formal and informal. Money assumes a dual function – a medium of exchange and an essential tool for circulating communist ideology. Communist currencies have remained important for circulating propaganda – banknotes are often highly attractive, featuring designs glorifying ordinary workers, soldiers and mothers. Landscapes showing agricultural productivity, industrial progress and military prowess are all designed to demonstrate to ordinary citizens how much life has improved under communism.

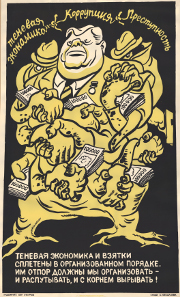

Communism looks to end wealth inequalities by abolishing private wealth, land and property ownership, regulating prices and state controlling industries and national service. The devaluation of the state currency is a natural consequence of limited foreign exchange and because many services – such as housing, education, public transport and welfare – become either free or are heavily subsidised by the state. Fragmentation of the monetary system was particularly pronounced during the Cold War, when conventional supply chains from capitalist countries were closed off for long periods. Frequent shortages of some foodstuffs and goods meant that there was not necessarily anything a person could purchase with money and periodically led to payment substitutes such as voucher systems. Visitors to the USSR in the 1970s found that US-made jeans or cigarettes were widely accepted as payment, while spirits such as vodka were added as a ‘sweetener’ to many a transaction. Citizens frequently turned to the black market to procure certain items – western clothing, good quality coffee and cosmetics. It has been an illicit and yet important component of most communist economies.

none

Bank of Yemen, 5 dinar, 1984. South Yemen’s currency was not updated after it became communist, so designs still carried the boat with Aden in the background imagery familiar from earlier banknotes. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

States under communist rule have tried to erode the status of money as a measure of value. Although they never succeeded in eliminating money altogether, they have taught citizens to question its role and function in society. In East Germany for example, coins were deliberately made from aluminium so that they felt light and ‘cheap’. In the USSR adverts for state savings banks deliberately avoided mention of customer benefits such as interest payments. Ideologically at least, savings accounts existed for the benefit of the state, not the individual.

Order of Labour Glory, USSR, 1985. This medal was issued to a female machine builder in Donetsk, Ukraine. As a recipients of all three classes of the Order of Labour Glory, she received a pension increase, priority on the state housing list, free public transport, a free annual pass to a sanatorium and one first class round trip flight per year. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Stalin said that ‘[t]he Soviet people have mastered a new way of measuring the value of people… not in roubles, not in dollars [but] according to their heroic feats.’ In the 1930s Russia introduced a complex system of awards and honours, emulated by almost all other communist countries, as a substitute for cash bonuses. A worker who exceeded their factory quota might receive the Order of Labour Glory, while a mother who reared nine children would be bestowed with the Order of Maternal Glory, First Class. Such awards were highly coveted because they came with ‘perks’ such as free travel. They conferred enhanced social status on their recipients and hence access to a better quality of life.

Shadow economy, corruption and crime By Boris Yefimov, Russia, 1990. In the USSR a degree of illicit economic activity was tolerated, at least until it threatened to destabilise the political order. This anti-corruption poster was issued at a time when the Communist Party’s grip on power was at its weakest, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The collapse of the Soviet Union had a domino effect, bringing communist rule to an end for millions around the world. During the transition to democracy and capitalism in the early 1990s most former communist states experienced profound upheaval. Questions were raised about historic ownership and whether property should be returned to its former owners, or to those currently occupying or farming it. Economies collapsed and homelessness escalated. Most former Soviet republics launched new currencies, while former satellite states redesigned theirs, some of which were highly politicised featuring local landmarks and national heroes. Lithuania’s first post-Soviet currency features an image of Juozas Zikaras’ Statue of Liberty. The original monument had been erected to celebrate Lithuania’s declaration of independence from Russia in 1918, and was deliberately destroyed by the invading Soviets in 1940.

Today, China, Laos, Vietnam and Cuba still identify as communist, albeit with near-normalised trading relations with capitalist countries. Since the 1990s, state control on their economies has loosened and commercial enterprise and consumer culture have flourished.

Thomas Hockenhull, Curator of Modern Money at the British Museum, was awarded a grant by the Art Fund through the New Collecting Awards programme in 2016. This has enabled him to build a collection of numismatic material from socialist and former socialist governed countries. His most recent acquisitions include Soviet posters advertising state banking services and a medal commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall, which will be included in this display. Other acquisitions include the first banknote to enter the collection from South Yemen, a 50 yuan note from 1980 featuring an intellectual, a female peasant and an industrial labourer, a rare 5,000 dinar note of Yugoslavia from 1950, and Yugoslav bon (coupons).

The display runs from 19 October 2017 to 18 March 2018 in Room 69a, entrance is free.

For further information on the display go to the British Museum website.

The rise of communism in Russia was fueled by many problems in Russian society, as you can learn in this podcast.