December 21, 2017 – At the launch of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and Treasure annual reports at the British Museum, John Glen MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Arts, Heritage and Tourism, announced that the number of new Treasure discoveries by members of the public had hit a record level, with 1,120 finds in 2016. This is the highest annual figure since the Treasure Act came into law exactly 20 years ago. In addition, there were a further 81,914 archaeological finds recorded through the Portable Antiquities Scheme across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The vast majority of Treasure finds (96%) and PAS finds (88%) were discovered by metal-detector users.

Also announced was an updated Code of Practice for Responsible Metal Detecting in England and Wales, which provides guidance on best archaeological practice for finders.

Piddletrenthide hoard coin sample.

The Treasure Act (1996) marks its twentieth anniversary this year, having come into law in 1997. The Act was created in order to make it easier for national or local museums to acquire important finds for public benefit. Of the 14,000 Treasure finds over the past 20 years, 40% are now in museum collections which can be enjoyed by local communities and the wider public. These include some of the most well-known archaeological objects in the country, such as the Staffordshire Hoard, a spectacular hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver war gear which has been displayed across the UK and in the USA, and the Frome Hoard, the largest collection of Roman coins in one vessel ever found in Britain.

Piddletrenthide excavation. © RMA Trevarthen Archaeological Services 2016.

Over the past 20 years, Treasure and PAS finds have significantly added to our knowledge of the past. For instance, they have offered us a greater insight into ancient trade networks between England and Continental Europe during the Bronze Age, and have also provided the means for us to fundamentally reassess the nature of early medieval trade. Over 1.3 million (1,312,332) PAS finds have been recorded, from prehistoric stone implements to post-medieval buckles, and all are available online for free at finds.org.uk/database. To date over 600 research projects, including 126 PhDs, have made major use of PAS data.

Driffield Hoard in situ.

Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum, said “The PAS is a unique partnership between the British Museum and our national and local partners. Its main aim is to advance knowledge, but the Scheme reaches out to people across the country, and helps bring the past alive. The British Museum is passionate about the PAS and what it achieves, for archaeology and local people.”

John Glen MP, Minister for Arts, Heritage and Tourism, said “Twenty years after the Treasure Act came into force, it is fantastic that Treasure discoveries have reached a record high. Thanks to the PAS, every year thousands of found objects are recorded so we can learn more about our past. I am pleased that a large number of the finds have also been added to museum collections and are on public display.”

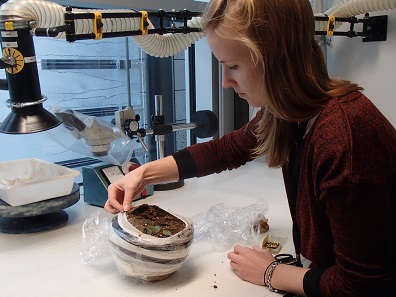

Piddletrenthide Hoard being excavated in the British Museum lab.

Michael Lewis, Head of Portable Antiquities & Treasure at the British Museum, said “Metaldetecting can make an immense contribution to archaeological knowledge, if practiced responsibly and the vast majority of people are keen that their hobby has a positive impact. The new Code of Practice for Responsible Metal-Detecting in England and Wales outlines exactly what is expected if people want to help archaeologists better understand our shared past.”

Finds on display at the launch

Two Late Bronze Age Hoards from Driffield, East Yorkshire which date to circa 950-850 BC.

A Driffield Hoard in situ.

One hoard contains 158 axes and ingots and is the largest hoard of its kind discovered in Yorkshire. Another consists of 27 axes and ingots. The two hoards were discovered close to one another by Dave Haldenby and were excavated by Kevin Leahy (PAS Finds Adviser).

A Driffield Hoard Axe.

It was first thought such hoards were collated to be re-used by metalworkers but now archaeologists think they might have been buried for ritual purposes. It is hoped that both hoards will be acquired by Hull and East Riding Museum, East Yorkshire.

Piddletrenthide in situ.

Roman coin hoard from Piddletrenthide, Dorset, of 2,114 base silver radiates found in a pottery vessel. The coins date to 253-296 AD, of which the latest issues include the earliest products of the newly established Roman mint of London.

Piddletrenthide excavation. © RMA Trevarthen Archaeological Services 2016.

The hoard was found by detectorist and author Brian Read, and block-lifted by Mike Trevarthen (a local archaeologist). It was unpacked and studied by conservators and archaeologists at the British Museum. This find was a rare opportunity to carry out a full archaeological excavation to try to discover more about why these coins were buried.

Winfarthing grave. © Tom Lucking.

Anglo-Saxon grave assemblage from Winfarthing, Norfolk which was found by Thomas Lucking while metal-detecting, and excavated archaeologically. This grave proved to be the burial of a high-status lady buried between about 650-675 AD.

Winfarthing pendant.

It includes a necklace made up of two gold beads, two pendants made from identical Merovingian coins and a gold cross pendant inlaid with delicate filigree wire. Most remarkable was another large pendant worn lower down on the woman’s chest. Made of gold, it has hundreds of tiny garnets inlaid into it in cloisonné patterns, including sinuous interlacing beasts and geometrical shapes.

Windfarthing pendant fittings.

Comparable to gold and garnet jewellery from Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire Hoard, it marks its wearer out as having been of the highest status in life, and through wearing a cross, among the earliest Anglo-Saxon converts to Christianity. Norfolk Museums Services are raising money to acquire this nationally-significant find for its collection at Norwich Castle Museum.

To learn more about the PAS visit the project’s website.

We also published an extensive article on 20 years PAS.

For more up-to-date news follow the British Museum blog.