In 1627 William V, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, took over the rule. His father Moritz had cared for books more than for the economy and ended up ruining the country. The new landgrave was faced with a mountain of debt and that at a time when large parts of his territories were occupied by enemy troops. William saw himself confronted with a sheer abundance of problems, which he intended to solve one by one, not with violence but with reason and diplomacy.

Hesse-Kassel, William V, 1627-1637. 10 ducats 1634, Kassel. Minted with double thaler dies. “Willow tree coin”. Apparently unpublished. Probably only one specimen in private hands. Extremely fine. Estimate: 200,000 euro. From Künker auction sale 279 (2016), 3210.

And it is precisely this situation that the emblem on the coin’s reverse describes, a willow tree bending with the wind in a storm. We have seen such willow tree engravings on coins of many different denominations: as thalers, multiple thalers, thaler fractions, as ducats, multiple ducats and guldens. It seems that the 10-ducat piece that Künker offers for sale at its Auction 279 on June 23, 2016, has not been edited until now. No other exemplar in private hands is known so far. Thus, this illustration was very important to the landgrave of Hesse. It represents his take on the situation. We are dealing with an emblem here, a popular means of pictorially representing a personal mind-set in the Early Modern Period.

Emblem: Better bend than break.

In the Early Modern Period an emblem was a sort of picture puzzle that could only be solved with the necessary educational background. While motto and image always belonged with interpretive verses, in most cases there was no room for the verses so that the observer needed all of his knowledge to interpret the depiction.

An educated contemporary of William would have been immediately reminded of an emblem entitled “Better bend than break” that had been published in a book by Adrian de Jonge in 1565. The illustration shows a broken tree while the slight reed next to it successfully resists the wind by bending with it. The accompanying explanation in Latin reads, in translation: “The mighty Boreas in a terrible storm overthrows the oaks trying to withstand him; but the reed stands unmoved and unbroken, despising him. He who is patient wins by evading him who is angry.”

William had not simply copied the emblem but adapted it to his purposes. Since he was a believing Calvinist, God’s name played an important role – both textually and pictorially. We see a willow tree in a raging storm but touched and protected by God’s name. God willing, my humble self will be elevated by him, the motto reads. So the believing Calvinist hoped that by God’s grace he would be given the strength to yield and thus overcome adversity.

It has sometimes been claimed that the die cutter did not know much about palms and created a willow instead of a palm tree. Nothing could be further from the truth. Every artist had his lexicons and his pattern books that he consulted when designing a new coin motif. And that was only if the educated client had not already done the work for him. Coin motifs were a matter for the top authority. For the sovereign they were a means of displaying his education. And William V was highly educated. He was a member of the Fruitbearing Society, the first German society of scholars, modelled on the Italian example and counting numerous aristocrats among its ranks.

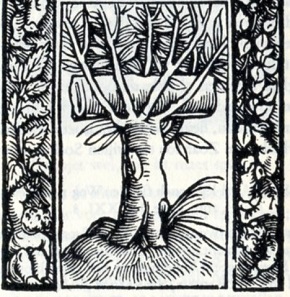

Emblem of the Fruitbearing Society. Source: Wikipedia.

The escutcheon of the Fruitbearing Society, which also called itself Palm Order, is a typical example of an emblem. The motto reads: Alles zu Nutzen (“To use everything.”)

The depicted coconut palm is still known today for the fact that you can use all of its parts. The accompanying verses are (in translation): “The name fruitbearing so that each and every one, who joins our ranks or intends to do so, try his very best, … to bear fruit.” The coconut palm was to remind those in the know that they, too, should bear fruit like the palm tree.

Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg. John Frederick, 1665-79. Reichsthaler 1673, Clausthal. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euro. From Künker auction sale 278 (2016), 1789.

On a Reichsthaler from 1673 the date palm, not the coconut palm, was used by John Frederick of Brunswick-Lüneburg in a very different meaning. The motto here is “Through hardships to the stars”. The date palm represents the difficult path to sweet success. Its trunk is rough and has no branches which would make the climb easier. He who wants to reach the sweet fruits must go a long and difficult path before, made even harder by the mountain.

Waldeck. George II, 1813-1845. Kronenthaler 1824. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 400 euro. From Künker auction sale 278 (2016), 2228.

Yet another aspect of the palm presents itself to us on this Kronenthaler by George II of Waldeck and Pyrmont from 1824. Its reverse features a palm on whose crown rests a heavy weight. “The palm tree will thrive under heavy weights,” is the motto associated with this illustration.

Emblem: Bearing hardships with patience.

It means that while a weight will hinder the growth of a palm tree it will also make it stronger by resistance. George II may well have taken this saying personal. After all he tried to unite Waldeck and Pyrmont and had to reverse his decisions in view of the angry protests from the Landstände. This coin motif can be understood as an official statement on his backpedaling. He did not feel humiliated by his failure but believed the setback had only made him stronger.

Brandenburg-Prussia. Frederick I, 1701-1713. Silver medal year 1 (1701) by J. Kittel. Rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 2,500 euro. From Künker auction sale 278 (2016), 1653.

Let us take a look at one last medal, which we can interpret more easily with the help of our emblem lexicon. We are looking at a medal that Frederick I commissioned for the occasion of his coronation as King of Prussia in 1701. It features a cedar surrounded by his name: Frederick, King of Prussia.

Detail from 1653.

Next to it is another cedar with the name of the heir: Frederick II, Heir. An inscription below the king’s cedar reads “he builds”, the one below the successor’s cedar “he waits”.

The cedar belongs to the cypress family and has been known for its resilience to moths and vermin since antiquity. That is why, in the language of emblems, it distinguished a ruler who resisted the courtiers who tried to ingratiate themselves with him. So it is perfectly reasonable to assume that by associating the cedar with both their names Frederick was making a promise here, in his and his successor’s name.

Detail from 1653.

The vine and the elm tree around which it grows have a completely different meaning. The elm is associated with the name of the spouse: Sophia Charlotte Queen. The inscription below reads “she commiserates”.

Emblem: Love even beyond death.

The elm and the vine that grows around it symbolise how exactly she does that. It stands for the love of the loyal wife and her unconditional support for her husband, even after his death.

It seems like we have to learn a new language in order to rediscover the ancient and artful language of emblems. Fortunately the dictionaries of this language have been preserved for us and are easily accessible in new editions with comprehensive indices. It is worth browsing them to understand and interpret pictures that an educated person in the Early Modern Period could easily decipher.

You can find an auction preview on Künker’s Summer Auction here.

And here you can get to the Künker auction.