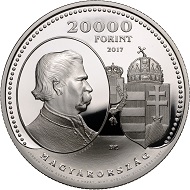

July 6, 2017 – To mark the 150th anniversary of the Compromise of 1867, the Magyar Nemzeti Bank is issuing a large 20,000-forint silver and a 2,000-forint non-ferrous collector coin.

Hungary / 20,000 HUF / Silver .925 / 77.76g / 52.5mm / Design: István Kósa / Mintage: 5000.

The front of the coin bears a portrait of Ferenc Deák inspired by the work of Ede Telcs, with a partially covered Habsburg coat-of-arms linking to the coat-of-arms of the Kingdom of Hungary. Minted in small letters, Ferenc Deák’s name is found on the lower border of the portrait, with the above quote by Deák around the bottom of the coin.

The back of the coin bears portraits of Queen Elisabeth and Franz Joseph I with the coat-of-arms of the house of Habsburg connecting the portraits of the royal pair to the Austrian coat-of-arms. The names of the pair are found below, with the script ‘KIEGYEZÉS’ (Compromise) around the bottom. On the upper half of the back, the year of the Compromise and the year of minting are located one above the other, with the last digit of these two years linked, denoting the occasion of this collector coin. The coin was designed by István Kósa.

Coronation of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth of Austria as King and Queen of Hungary, on June 8, 1867, in Buda, the capital city of Hungary.

The 1867 Compromise

The Compromise of 1867 is a catch-all term used for the agreements which reestablished the political, legal and economic relations between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary at the beginning of 1867. It was negotiated between the head of the house of Habsburg, Franz Joseph I, and the delegation headed by Ferenc Deák and Gyula Andrássy.

In the spring of 1848, the revolution that succeeded in Austria and Hungary resulted in the abolition of feudal relations in the Habsburg Empire and a shift towards a bourgeois society. However, after the Hungarian revolution was suppressed in 1849, under martial law the Austrians attempted to move forward with modernisation while exploiting the results in their efforts for ascendency in leading a unified German nation. The Austrians overestimated their power, because by that time they no longer fulfilled the conditions for being a great power and instead were only capable of being a regional power. Moreover, the Habsburg Empire was vulnerable because it had rigidly resisted the calls for self-government of the national minorities living within its territories for more than half a century. After its weakness was exposed by severe military defeats in 1859 and 1866, the Emperor and his advisors realised that restoring peace in Hungary was one of the key prerequisites for the continued existence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The negotiations led to the adoption of Law-Article XII of 1867, which stated that the person of the sovereign and the ‘Sanctio Pragmatica’ united the two sovereign nations. Based on the latter (specifically the hereditary lands of the Habsburg provinces), so-called common matters “arose”, such as foreign and military policy and the related financial aspects. The budget for the three joint ministers acting in these fields was to be negotiated by delegations from both parts of the Empire, and Hungary also agreed to assume part of Austria’s national debt. It would furthermore conclude a compromise with Austria which would be renewed every ten years and would unite the monetary systems of the two states (the Hungarian government concluded a separate compromise agreement with Croatia, which entered into effect in 1868). The ceremonial high point of the Compromise occurred on 8 June 1867, when Franz Joseph I was crowned King of Hungary in a lavish ceremony at the Matthias Church in Buda. According to the prevailing opinion at the time, Queen Elisabeth played a key role in the Compromise, exerting her influence in favour of the Hungarian interests.

The moral lesson of the Compromise of 1867 which endures to this day is that the political forces of two groups with serious conflicts of interests were ultimately able to reach a peaceful compromise thanks to their tireless efforts. This teaches us that there is essentially no political situation which is so complicated that the parties to the conflict cannot reach an agreement if they are able to subordinate short-term gains to the long-term goals of building a community. One of Ferenc Deák’s famous slogans captured political credo behind this: “I am more able to love my homeland, than to hate my enemies.”

For more information please visit the Hungarian Mint webpage.

And the historical background is further illuminated on the website of The World of the Habsburgs.