January 21, 2014 – Despite some initial difficulties, El Salvador replaced the $1 note with the $1 coin in 2011, which reduced costs by more than half. This article discovers why the changeover succeeded and why the same procedure is not applicable to the US or other countries’ monetary systems.

Much attention has been given to the debate in the US in recent years regarding the $1 coin versus the $1 note. However, irrespective of the various evaluations in recent years making the case for the former, it remains a debate because the public has shown that, as long as both the $1 coin and $1 note remain in circulation, they will choose the latter.

El Salvador, meanwhile, which has adopted the US currency, has undertaken its own evaluation, on the basis of which it replaced the bill with coin in a two year programme commencing in 2011. A case study on the programme was presented at ICCOS Americas in Miami by César Roney Fuentes, Head of the Treasury Department of the Central Reserve Bank of El Salvador (BCR).

El Salvador borders Honduras, Nicaragua and Guatemala in Central America. It has a population of 6.25 million, occupies an area of 21,041 km2, has a population density of 297 per km2, a gross domestic product of $23.8 billion and a per capita income of $3,805. Its currency was the Colón up until 2001, when it adopted the US dollar. Under dollarization, the BCR imports new dollars from the Federal Reserve and exports unfit banknotes, with the distribution and collection process being accomplished through a correspondent bank with a door to door service.

Once the dollarization process was fully established and stabilised, the BCR realised that around 40% of all banknotes imported and returned from the US each year were $1 notes. It decided, therefore, to undertake a study to see if it could reduce the cost of importing these, noting that the global trend was to substitute small bills with coins. It first looked at what was happening in other dollarized countries. It then evaluated the potential cost savings from moving from a $1 bill to a $1 coin, taking into account the cost of importing and exporting the $1 bills, the number of import and export operations involved in the process, the potential lifespan of the $1 bills, the feasibility of using $1 coins dispensing machines and all other aspects of replacing the $1 bill with a coin.

High costs of note

The evaluation confirmed the $1 note to be the most expensive in the dollarized system. It had a circulation life of less than one year, resulting in high replacement, import and export costs; in 2010 40% of import and 38% of export costs were attributable to the note. The domestic cost of handling the $1 notes was very high because it had such a high circulation rate within the system. In comparison, the BCR estimated that the $1 coin would have a circulation life of 18-20 years, requiring no exports in the medium term. The overall assessment was that a change from the $1 bill to the $1 coin would result in savings of approximately 45%.

2

Recognising the implications for all stakeholders, and particularly the public, of such a major change in the country’s circulating currency, the BCR planned the changeover process in advance to ensure that it went as smoothly as possible. It made arrangements to receive the currency into the central bank vault, reviewed and defined new distribution logistics to banks and the public, and held meetings with the country’s financial institutions, vending machine companies and all other stakeholders.

Once satisfied that the implementation process was sound, the BCR suspended the supply of $1 bills and embarked on a public education programme on the conversion to the coin using media interviews, radio spots, newspaper advertisements, online videos, posters and flyers with the characteristics of the $1 coin, billboards, advertising on buses, monetary education programmes and interviews with cash experts.

Difficulties with changeover

The changeover did not pass without some difficulties. The size and weight of the coin caused issues – there was some confusion with the $0.25 coin and also with coins in neighbouring countries. The use of the $1 bills in circulation increased as the public preferred them, and when they were returned to the BCR they exhibited higher than normal levels of deterioration. Use of the $5 bill also increased.

There were also difficulties with supplying a single $1 coin design (one design being preferable when introducing a new coin), because the Presidential $1 coins held in stock by the Federal Reserve banks had only a common reverse with various presidents on the front.

Moreover, the initial perception of the Association of Banks was that using the $1 coin would increase transportation costs, while there was a perception among the public of loss of value and of reduced efficiency in its use. Furthermore, the dispensing of $1 bills by ATMs had to be stopped and, as the $1 bill began to be in short supply, counterfeiting increased.

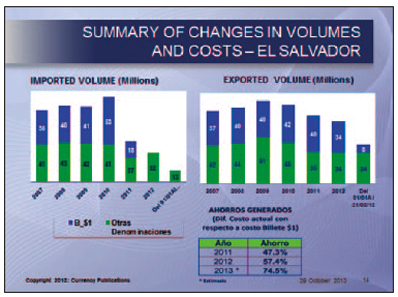

For the changeover, 57.2 million coins were imported from the Federal Reserve and 52.4 million $1 notes exported (see chart). In 2010, out of 91 million banknotes imported, 53 million were $1 notes. In 2011, the number of $1 notes imported was 18 million (out of 45 million) but, once the programme started, the import of $1 notes stopped.

The export of used $1 notes can also be seen to have reduced significantly in 2012 and in the first eight months of 2013. But it is the cost savings that really tells the story – 47.3% in 2011, 57.4% in 2012 and estimated to reach 74.5% by the end of 2013.

Key factors in success

In summing up, Mr Fuentes noted that the main objective of cost reduction had been achieved and that, despite some initial difficulties the coin had now been accepted by the population; they had come to understand that the coin lasted much longer, was easy to use, was not dirty in comparison to the heavily used $1 notes and, being more difficult to forge, increased confidence.

He also noted two key factors that led to the success of the programme – first the BCR’s decision not to provide any more $1 notes to the public once the introduction of the $1 coin commenced and, second, involving all of the stakeholders, especially the banking sector.

Questions for other countries

Two questions immediately come to mind. First, if such large savings can be made in El Salvador, couldn’t similar savings be made in the US? However, there are many differences between the two countries that make a direct comparison invalid – not least the fact that the $1 bill in the US lasts six times as long as in El Salvador, and that all factors involved in such an evaluation would be different in the two countries.

Second, why would all other dollarized countries not adopt the $1 coin to make such savings? Currency News posed this question to representatives from the Federal Reserve attending the ICCOS Conference. They indicated that a major reason the economics of a $1 coin worked for El Salvador was the low transportation costs involved. Such costs would vary greatly from country to country, as would virtually all of the other parameters, so each case would be unique and should be judged on its own merits.

This article was originally published in Currency News.

For more information or to subscribe, contact info@currency-news.com.