by Jennifer Gloede

January 18, 2018 – When people ask what I do for a living, I say, “I work at the National Numismatic Collection. It’s the Smithsonian’s collection of monetary and transactional objects.” People generally assume I’m talking only about coins, paper money, credit cards, and checks. I like to shock them by following up that statement by saying that one of my favorite objects in the collection is a taxidermy bird. The National Numismatic Collection (NNC) houses so much more than the monetary objects that we are most familiar with today. Here are my top five picks for the weirdest, most unexpected, and overall most bizarre objects in the NNC.

Quetzal bird (Pharomachrus mocinno), Guatemala, collected around 1923.

1. A feathered friend among the financial objects

This quetzal bird was transferred to the NNC in 1956 from our colleagues at the National Museum of Natural History. The quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala, but what does it have to do with money? The indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica used feathers from quetzal birds as currency. Quetzals featured prominently in Mayan mythology and symbolized wealth. In 1925 Guatemala changed its national currency from the peso to the quetzal, and the new quetzal banknotes feature an image of the bird on each note. This quetzal doesn’t come alive at night like in the movies, but regardless it is still a favorite object of mine.

Bouche-évier (Sink Stopper), Marcel Duchamp, bronze cast of lead original, 1967. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp.

2. A sink stopper with a high art pedigree

The NNC has an expansive collection of American and foreign medals commemorating various historical events, people, and societies, but it also includes medals that were created as art! That leads me to the somewhat odd and surprising object pictured above, a medal designed by famed artist Marcel Duchamp. (You know, the same guy who presented a urinal as art and titled it “Fountain.”) Duchamp created a series of works called “readymades,” which were ordinary objects that he transformed into art. This medal was the fifth of 100 cast in bronze from a lead original created by Duchamp from his sink stopper.

Napoleon death mask, made by Francois Carlo Antommarchi, 183.

3. A familiar French face

You might expect that the NNC would have coins and medals that feature the likeness of Napoleon Bonaparte, but our collection holds something even closer to the original: a plaster copy of his death mask! Napoleon held many titles, most prominently Emperor of the French. He died in 1821 in exile on the British island of Saint Helena. At that time it was a common practice to make a death mask of notable figures who passed away. At the time of death, Napoleon’s physician, François Carlo Antommarchi, cast one mask. He later produced copies, like this one made in 1833. But why is it in the numismatic collection? There is a small medal embedded at the base of the neck with a portrait of Napoleon wearing a laurel wreath, the name of the physician, and the date. I see a lot of faces on coins and currency, but rarely does my work involve something this realistic (and creepy)!

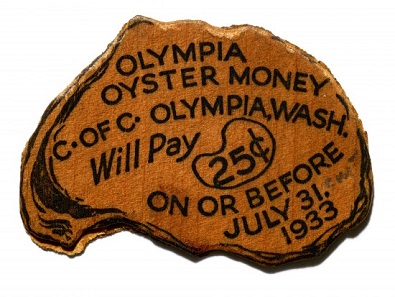

Oyster money from Olympia, Washington.

4. Can you spot me a few clams, pal?

The Great Depression saw a variety of new currencies develop in the United States. The banking crisis led communities to creative solutions for bartering and exchange. In Pismo Beach, California, they made clamshell money. Similar to the clamshell money, this oyster money is a creative currency from Olympia, Washington. Made out of wood and designed to look like an oyster shell, this object was worth 25 cents. Other Pacific Northwest cities including Raymond and Tenino, Washington, issued similar currencies at the time. Honestly, if someone offered to pay me in clams or oysters, I’d probably take that as payment!

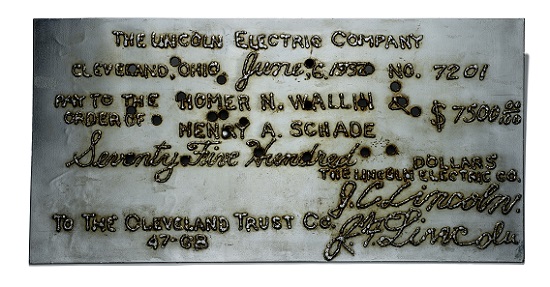

USD7,500 steel check, Cleveland Trust Company, 1932.

5. One giant check

Checks are not completely surprising things to find in a numismatic collection. But a two-foot-long check made of steel? That’s pretty unexpected, and very heavy! This check, dated June 6, 1932, was made out to Homer N. Wallin and Henry A. Schade, who were the winners of a welding contest. More than welders, Wallin and Schade were naval officers who applied their skills to ship construction, repair, and salvage. The president of the Lincoln Electric Company, which hosted the welding contest, signed the check by arc welding, and Wallin and Schade endorsed it in the same way.

These and many more fascinating objects in the National Numismatic Collection are ready to be researched!

Jennifer Gloede is the outreach and collections specialist for the National Numismatic Collection. To learn more, view her profile.

This post originally appeared on the blog of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. To read more about coins and money in the museum’s National Numismatic Collection, click here.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History also possesses a specimen of clamshell money Jennifer Gloede mentions in the article. More information is available here.