November 3, 2016 – The British Museum shows a new exhibition until 7 May 2017 in Room 69a: ‘Defacing the past: damnation and desecration in imperial Rome’ presents coins and other objects that were defaced, either to condemn the memory of deceased Roman emperors or to contest the power of living ones. Images of power have always been used as a medium for propaganda; the power that they convey could backfire if they were used against the authority by which they had been designed and propagated.

Bronze as of Tiberius featuring the consulship of Sejanus, whose name was erased after his downfall; Bilbilis (Spain), AD 31 (loaned by the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna).

The display is supported by Stephen and Julie Fitzgerald and research funded by the Leverhulme Trust. It will examine Roman history from the view of the defacer, looking at objects from Sejanus in the rule of Tiberius to the decadent Caligula and Nero, and from the disastrous Domitian and Commodus to the soldier emperors of the later empire.

Copper as of Nero countermarked on the portrait’s neck with SPQR (The Senate and the People of Rome) after his downfall; Lyon (France), AD 65. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Like many rulers, Roman emperors used inscriptions, sculptures and coins to project their authority. The imperial image conveyed through these media could be contested and subverted for political and religious reasons.

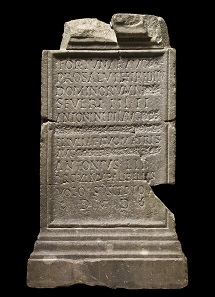

Marble Latin inscription dedicated to the well-being and safe return of Septimius Severus, Caracalla and Geta, on which the names of Geta and Plautilla have been erased; from Rome, AD 202-205. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The memory of Roman emperors and high-ranking officials could be officially condemned after their death through a process known as ‘damnatio memoriae’, meaning that a person’s memory was attacked and largely erased through physically erasing names and defacing portraits. This affected in particular rulers who were overthrown and murdered or executed. Imperial images were also mutilated and destroyed by Rome’s enemies to contest the imperial authority.

The free display will show the history of the custom of mutilating and subverting images of power with objects from Egypt, Mesopotamia and Greece, focusing on the Roman Empire.

Objects include coins of Caligula and Nero, the first emperors who suffered from ‘damnation’ after their death, as a consequence of their unpopularity with the Roman Senate and the army.

Bronze medallion of Commodus struck from two alloys and set in a wider rim, showing his facing bust, whose face has been erased; Rome, AD 191. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Other coins on display show examples of defacement of images of Domitian and Commodus, both killed in conspiracies as a result of their authocratic and extravagant behaviours.

Bronze coin of Domitian and his wife Domitia from which face of the emperor has been erased; Cibyra (Turkey), c. AD 93-96. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

For example, the bust and name of emperor Domitian were erased from bronze coins on which he was portrayed face-to-face with his wife Domitia, who is believed to have been involved in the plot to kill him.

Bronze coin of Caracalla and Geta facing each other on the obverse, from which the bust and name of Geta have been erased; Mytilene (Turkey), AD 209-211/212. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The show will also offer a broad range of examples of defacement of Geta, son of the emperor Septimius Severus, whose memory was fiercely erased after his murder by order of his brother and co-ruler Caracalla. These include several coins from the provinces of the Empire and Egyptian papyri on which his name was deleted. Lastly, a marble Latin inscription dedicated to Septimius Severus, Caracalla and Geta, on which the names of Geta and Plautilla, Carcalla’s wife, have been removed will also be on display.

A catalogue published by Spink in collaboration with the British Museum will accompany this exhibition.

Fore more information go to the British Museum website.