Human Faces Part 1: The Father of the Gods, Zeus, in Olympia

with the kind permission of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

Why is it that for centuries – or, rather, thousands of years – the head has served as the motif for the side of a coin? And why has this changed in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann poses these questions in her book ‘MenschenGesichter,’ from which the texts for our new series are taken.

Olympia. Coin of the guardians of the Shrine of the Eleans (Peloponnesos). Stater, around 360 BC. Head of the bearded Zeus of Olympia with laurel wreath facing left. Reverse, Eagle sitting, facing right. © MoneyMuseum, Zürich.

When we think of Olympia today, we immediately think of the Olympic games. In our mind’s eye we envision noble youths racing one another or competing in wrestling matches. And yet, it started off very differently.

Reconstruction of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, as it was imagined in former times. Source: Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau, Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 14th edition. 1908.

It’s said that in mythological antiquity, Apollo and Heracles constructed a temple for Zeus in Olympia in which a son of Apollo prophesied the future from the flames of the sacrificial fire. The descendants of this first priest acted as sort of an army chaplain in historical times, accompanying Greek armies and settlers throughout the entire known world of the time. We know, for example, that emigrants who sought a new home in Syracuse were accompanied by an Olympian priest, and that prior to the Battle of Platae, which saw the united Greek forces defeat the Persians in the year 479 BC, a priest from Olympia had determined the will of the Gods.

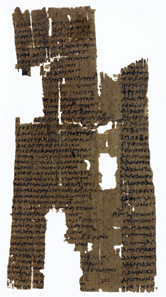

Ancient list of Olympic champions from 480-468 and 456-448 BC, third century AD. Source: Wikipedia.

Many political communities were indebted to Zeus of Olympia for exerting his influence through his priests and aiding in their existence. And naturally, the communities all showed their gratitude – they sent the God opulent votive offerings and on the occasion of the great festival in his honour that took place every four years, sent a festival delegation. And seeing as competition was a part of every proper Greek celebration, naturally the best athletes of every city were represented in the Olympia events. This was the origin of the illustrious Olympic games, which therefore attracted the best athletes from across all Greek-populated areas of the world.

Statue of Zeus by Phidias, Redrawing of a coin from Elis. Source: Baumeister, Monuments of Classical Antiquity, vol. 3, 1888, p. 1316 / Wikipedia.

The image of Zeus as a bearded man in his prime that confronts us here is influenced by the famed depiction of Zeus created by Phidias in the middle of the 5th century for the Temple of Olympia. This gold-ivory statue that, incidentally, was never a venerated idol but merely a precious votive offering to the Olympian Zeus, was among one of the Seven Wonders of the World in ancient times. It was viewed by countless Greeks. They were all so impressed by it that soon no one in Greece could imagine Zeus any other way than how he was depicted in the statue by Phidias.

In the next chapter, Zeus’ daughter Athena, protectress of the city of Athens, takes centre stage.

All sections of the series can be found here.

The book ‘MenschenGesichter’ is available in printed form from the Conzett Verlag website where you can find it as an ebook too. It soon will be translated to English.